by Michael Juliani

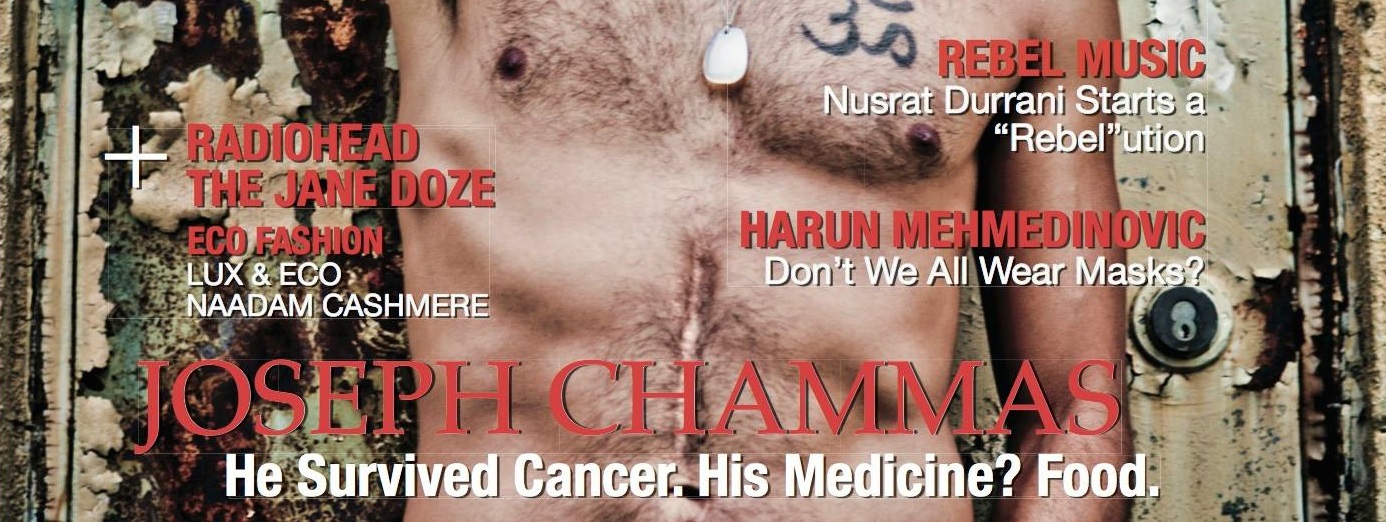

The Huffington Post: Photographer Harun Mehmedinovic Seeks the Sublime With Bloodhoney* Book Project

For 60 days, the photographer Harun Mehmedinovic is focusing on his Kickstarter campaign and not much else. He usually doesn't sleep much anyway, a habit he's had since moving to the United States at 13 after surviving four years of the Bosnian War. Living in Flagstaff, Arizona, teaching film and photography at Northern Arizona University, he spends most of his days sending messages to hundreds of people, asking them to pledge to buy something from his campaign to fund the printing of his second book, Persona. Most people don't respond.

There are misconceptions about contributing to a Kickstarter campaign, that it's like donating to a cause. And because you're buying a product directly from the person who made it, there's an anxiety about his self-indulgence. The price that Harun set for the reward of one digital copy of the book and one print copy ($50) is likely less than what it'll eventually be sold for in a bookstore. The minimum monetary goal for funding his project, $20,000, actually lies much lower than what he hopes to make, about $35,000. Whenever people contribute, Harun thanks them publicly on his Facebook, always adding the link to the Kickstarter page.

I'm part of Harun's project. After I wrote an article about him for the Los Angeles Times in May 2012, we kept in touch and worked together on a photo and text essay about rites of passage for an issue of Blindfold Magazine. He decided to launch a series of books about his photography project, Bloodhoney*. He asked me to edit the text that would accompany his images. Through Kickstarter Harun was able to fund the limited printing of his first book, Séance. This September he distributed print copies to those who had backed the project while simultaneously launching the second Kickstarter, for Persona.

Harun and I first met because of his father's writing. I had been reading the book Motel Chronicles by Sam Shepard all fall of my junior year in college. A smattering of poems, short stories, monologues and dialogues, it unlocked a certain vault of my subconscious. It seemed so personal that I thought it must not exist for anyone else. In an interview I found, Shepard was asked about other writers he admired. He mentioned Semezdin Mehmedinovic, who he said was Serbian, and had written a book called Sarajevo Blues:

"He accomplished the kind of book I've always tried to do and haven't totally succeeded at, which is a combination of poetry, prose, short stories, diary, all thrown into one thing. I love that form. He actually managed to do it with Sarajevo Blues. During that horrible conflict he chose to stay there in the city. He had a wife and kids and decided to stick it out. It's an amazing account of a writer under fire."

Enough said. I went online and ordered the thing after learning that no local bookstores had it in stock. Rooted in Mehmedinovic's reading of translations of American literature, including Jack Kerouac's Mexico City Blues and, yes, Shepard's Motel Chronicles, Sarajevo Blues collects dispatches from a shattered world, Sarajevo during the city's four-year siege in the Bosnian War. In fact, Mehmedinovic decided to stay in Sarajevo with his wife Sanja and nine-year-old son Harun (they were not, as Shepard thought, Serbian).

When I read Sarajevo Blues for the first time, it was 2012. I wondered what had happened to the Mehmedinovic family, who had supposedly come to the United States. Through Google I learned that Semezdin's son, Harun, who made poignant appearances in Sarajevo Blues, including a scene where Semezdin finds gray hairs in the 10-year-old boy's head, had attended UCLA film school and the American Film Institute. He had made a short film about the Bosnian War and was now in the middle of a photography project called Bloodhoney*. He was on Facebook and was now 29 and living in Los Angeles like me. I was taking a feature writing class for school at the time and needed a story to tell. I wrote Harun an email.

We met up at a Brazilian restaurant in Culver City. I brought Harun's father's books with me along with notepad and tape recorder. Dressed in black with a messenger bag slung over his shoulder, Harun was tall and lanky with his hair pulled back in a ponytail. I had never known anyone who had survived a war, never mind one where children were prime targets for snipers. To rebel against the most terrifying aspect of the war, Harun and his friends used to tempt the snipers by running across streets where bullets often flew. They'd play rock-paper-scissors for who could go first, when the sniper wasn't paying attention. The others would follow. Though many kids died playing this game, Harun told me that such rebellion against the status quo of fear was necessary to keep sane.

At the Brazilian restaurant, we ate and talked for four hours, till the waiters locked us out.

Harun's photography project proved to be about more than capturing the saturated, incandescent beauty I'd seen in shots posted on his website. At dinner Harun explained that his project was rooted in the sense of adrenaline he'd had as a kid during the war, amidst the collapse of the social fabric. He had spent his adolescence in Phoenix and then in Alexandria, Virginia, and he had been lonely, angry, and frustrated by his inability to match the primacy of the war zone. In school he argued with teachers, got in fights, and kept to himself, watching films and planning his own path to Hollywood.

After some success with his short film, In the Name of the Son, Harun kept crisscrossing the country, traveling ceaselessly as he'd done since landing in the United States, taking pictures of landscapes and skies. In his mid-twenties he found himself more cooped up than usual, reading lots of articles on the Internet, working on film scripts, realizing that he'd worked himself into an uncomfortable isolation. On the film festival circuit he reconnected with friends from college who were broken down by nine-to-five jobs.

Over a series of hours-long interviews I did with Harun in March and April 2012, I began to see how he had combined his filmmaker's sense of vision and intellectual grasp of philosophical sources like Joseph Campbell and Rumi with a deep personal need to re-connect with the end-of-the-world adrenaline of those four years of his youth. Realizing that a film project would be too difficult to manage, Harun grabbed his camera and asked friends to pick any location they wanted and any clothing they wanted. He would follow them for up to 15 hours straight, giving time and space for them to dissolve the anxieties of their day-to-day lives. After doing dozens of these shoots all over the continent, he could pinpoint certain series and images that had captured some sublime quality reminiscent of the open-world beauty present in chaos.

In the United States, stability is often promoted as wellbeing. The privilege of being able to live mostly free from violence and societal chaos allows people to rest on what they have. There are rarely opportunities to challenge this way of life unless a person faces himself and breaks down some very tense barriers. Even though I hungered to break down my own walls, I intrinsically feared the ardor and instability it would require, even for just 10 hours. When I interviewed a handful of people who had been subjects of Harun's shoots, I heard about the difficulty some had had becoming vulnerable. Some even recalled specific images that cropped up: the bar scene, their families, the clothes they wear to work.

One of my favorite passages from Séance was the story of a 21-year-old woman named Bri.

When Harun got in touch with Bri, I remember him telling me that her parents had grounded her. "She's 21!" he exclaimed. "How do you ground someone who's 21?" Wholeheartedly in love with and in need of dance in her life, Bri's passion had interfered with her family's hopes for her future. She told Harun about having to hide her dancing, containing it to private moments in front of the bathroom mirror and even on her way to school, where she was free to act as she pleased. The first shoot Harun did with her was in a lake, where she contorted her body as if moving to music. A far-off kayaker sat and watched, and when the shoot wrapped the kayaker applauded.

I could tell that Harun cared a lot about Bri's story. Bri was a free spirit trapped by her circumstances, by a situation that continued to deprive her of control. Even though their backstories were so different, and even though the plight of an American millennial seems to pale in urgency compared to a refugee's, I could see the frustrated child in Harun connecting with Bri's desire to break free. At the root, they had known the same frustration, and their acts of rebellion were identical if not exactly in scale.

"In America, you are taught to fear and obey, same as in any other place," Harun told me. "My rebellion was against fear and so is theirs. They are, in essence, afraid to live. The sniper bit is a thing a child would do, and in itself it means keeping the youth alive. For most people, that experience on the shoots is about childhood, literally. They become children again. It means that certain fears just slowly vanish."

Persona will focus on a specific element of the project: some people show up to shoots dressed as a sort of character. This element bothered Harun at first, begging him to wonder whether the characters represented a more authentic representation or a retreat from who the people really are. Harun said, "Let's face it; we all wear masks every day. We probably wear a different mask for every person we meet. We probably wear a mask for every place we go. Very rarely do we share with others who we really are. Very rarely do we feel confident and courageous enough to just be ourselves." The book will explore the shoots where this was relevant, providing details from the lives of the people involved.

I have yet to experience a shoot--we've made plans, but Harun's travels are so impulsive that he's often only in town somewhere for a night or a couple of days. I've realized that the deeper I become entrenched in Harun's perspective on the world, the more I benefit from it. For awhile, before I knew him, and when I was getting to know him, I still felt like his frame of reference wasn't so foreign to me, even though he had survived one of the most drastic wars in recent history.

I think, more than anything, the Bloodhoney* project offers people the chance to have a transcendental experience. The name itself refers to the word "Balkan," a combination of the Turkish words for "blood" and "honey." Harun said that if you are living a full life, it will be bittersweet. You will be feeling the good things and the bad things, and you will have escaped the monotonous gray area where nothing is felt at all.

Having found an outlet during the war, Harun found that vein again here, where rebellion against the status quo isn't as easily pronounced. And instead of coveting it, he offers it to anyone who has a free day, some favorite clothing, and an ideal location in mind.

The Huffington Post: Photographer Harun Mehmedinovic Seeks the Sublime With Bloodhoney* Book Project